Saturday, May 17

Start: Ichupata 13.55274 S, 72.553491 W 14,768′ (4,502m)

Via: Incachiriaska Pass 16,278′ (4962m)

Via: Sisaypampa ~14,000′ (42670m)

Stop: Paucarcancha 10,270′ (3130m)

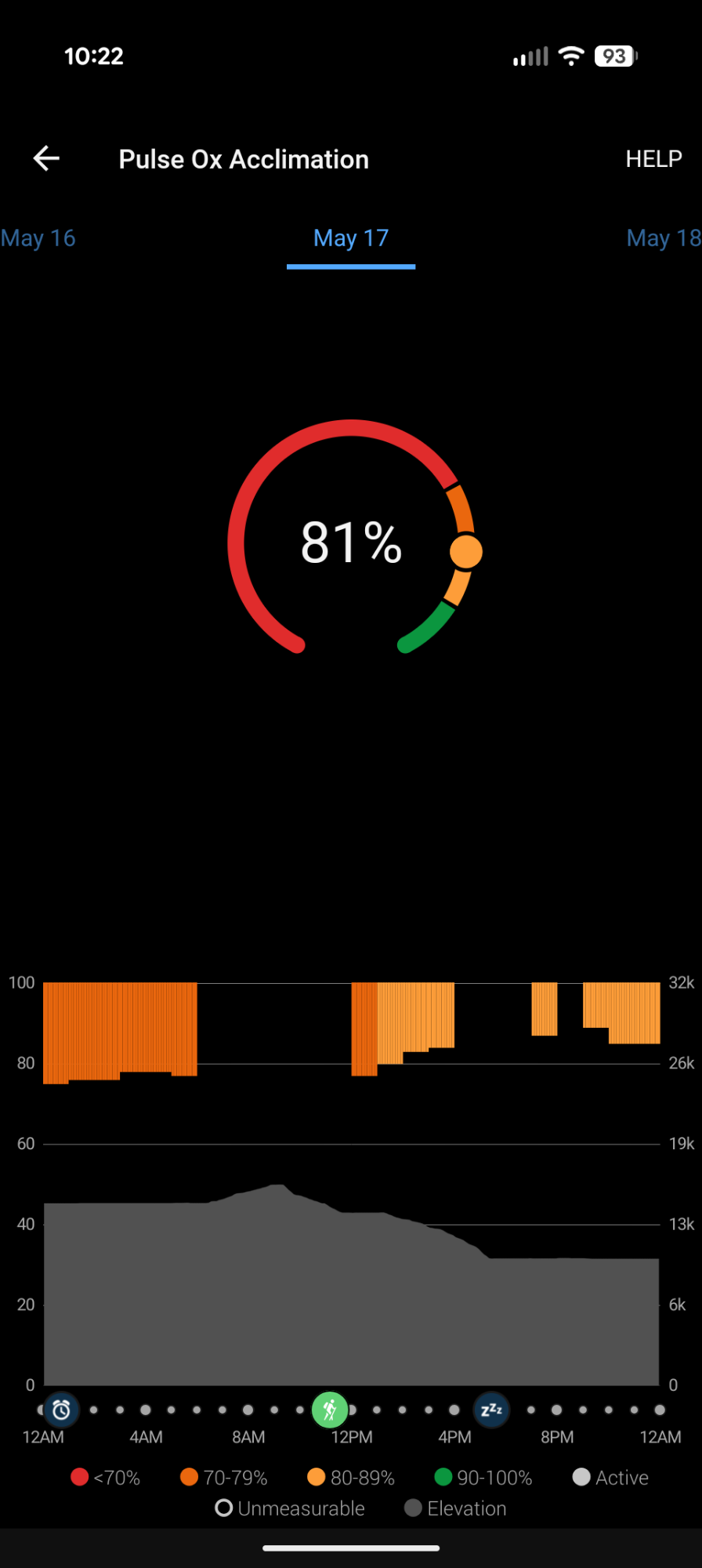

O2 average 81%

11.65 miles

1,633′ ascent

6,036′ descent

It’s always hard to fall asleep after a full day of hiking. I toss and turn and eventually fall asleep. I kinda wake up and work hard to convince myself that I don’t need to pee. I eventually give in and emerge from my warm cocoon about 1 am. There’s already an icy crust on the outside of my tent and I sorta crack my way out. I carefully make my way over to the toilet tent and when I emerge I take a few frigid minutes to admire the star-studded sky.

Breakfast is scheduled for 5:30 am and the crew says they’ll wake me at 5 am. I set my alarm for 4:45 am so I’ll have enough time for morning rituals like taking medication, putting a little sunscreen on my face, stuffing my sleeping bag in its stuff sac, changing clothes, loading my duffel. After crawling out of my tent, I move my duffel and backpack to an icy tarp that is laid out. With the aide of my headlamp, I carry the warm cup of coca tea that was delivered to my tent, with me to breakfast. As we eat eggs and oatmeal, the morning starts to glow through the mess tent walls.

There’s a tiny area in the wispy clouds over Apu Salkantay that briefly flickers the faintest rainbow. And the moon shines brightly over Humantay. I’m ready several minutes before Elizabeth and I wait until the last second to take off a warm layer.

Elizabeth and I leave just after 6:30 am and climb up to the trail above camp. In the below photo, please note the lateral moraine between us and Humantay (left) and snow-capped Apu Salkantay (right). Keep an eye on these features as points of reference in the pictures to follow.

We climb a short distance before making a right turn where multiple lateral moraines become visible. Elizabeth tells me a story of a massive debris flow that was powerful enough to harm people and homes down the valley to our Northwest. She points out all the rocks and debris that now sit atop the lateral moraine on the opposite side of the one directly in front of us. It’s not hard to imagine that due to glacial recession and destabilization these kinds of events will be more and more common.

The sun finally reaches me and I shed my patagonia wind layer. I point out a large bird high in the sky and Elizabeth says that it’s an eagle. It floats over the mountains to our right and out of sight. At this high altitude, the vegetation is sparse. And there’s a couple birds that keep flitting away from me every time I try to take their picture. About an hour and a half after leaving camp, I turn around to a sound behind me. Elizabeth has an oval earthen whistle and calls to Earth Mother Pachamama and all her beings. Apu Salkantay good morning! Little birds good morning! Small flowers good morning! Laguna Salkantay we greet you! Apu Salkantay allin p’unchaw! Huch’uy pisqukuna allin p’unchaw! Huch’uy t’ikakuna allin p’unchaw! Laguna Salkantay napaykuyku!

In Quechua culture, Apus are revered mountain spirits seen as protectors of communities, capable of influencing weather and natural elements. Salkantay translates to wild or savage which was noted for its wild and untamed spirit.

My upward progress is slow but steady. About 8:30 am, I look back and can see the little dots of our team ascending behind us. Now note my position compared to the lateral moraines and Humantay. The sun slowly reaches over the 20,574 foot crest of Apu Salkantay and makes her turquoise glacial-meltwater lakes really pop. I stand admiring the scenery while also catching my breath. I hear a loud noise and see an small ice cloud billow up as ice slides down the face of Salkantay.

Elizabeth points out a venado cola blanca or white-trailed deer far far below us near the edge of Laguna Salkantay. Several switchbacks before Incachiriasca Pass, Oscar, his horses and the whole crew catch up and pass Elizabeth and I.

There’s a couple horses near Incachiriaska Pass that aren’t part of our team and their owner is nowhere in sight. The sun turns their manes into lines of liquid gold. Just below the last switchback is this high-altitude plant which ironically is known by two different genus names Senecio and Culcitium. It has these wonderful furry and spongy leaves that I just want to reach out and pet. Unfortunately, the flower stalks are not yet open.

Above: small ice fall (left) and Apu Salkantay summit (right).

At 8:50 am we crest Incachiriastca Pass. My Garmin watch lists our elevation as 16,278′. Oscar’s girlfriend continues on with the horses while Elizabeth comments that she’s never seen such a clear and beautiful morning here with Salkantay.

Elizabeth takes our group photo atop the pass and then while holding three coca leaves we all make offerings and prayers to Salkantay and Pachamama. Elizabeth again blows her whistle. I notice Juvenal collect some of the Senecio plant that’s right at the top of the pass and Elizabeth comments on its medicinal benefits.

Oscar, Joel and Juvenal all make quick tracks down from the pass and soon disappear into the scenery. Not long after the rest of the crew, Elizabeth and I start the descent at 9:20 am. I trot downhill through rocky trail for numerous switchbacks before stopping and looking back. Magestic Salkantkay looms large behind us.

The steep descent flattens out and the trail meanders through the carved upper canyon of Pampacahuana Valley. While not the famous Inca Trail, this trail was frequently used by the Incas. The sweeping canyon is filled with small flowers and bunchgrass mounds. It’s impossible not to notice in this barren environment, the club moss Lycopodium, whose tall reddish body shouts hello I’m over here!

Above: Gentians (blue), Saxifraga? (yellow), Werneria (white)

Below: Baccharis, Planatago rigida or water mattress in the plantain family, Ephedra americana

If you look closely, there’s lots of life in this high-altitude Puna zone. Several kinds of crustose lichens are painted onto rocks and Conyza is standing tall, with its yellow cone flowers getting ready to bloom. Clouds start to billow up and frost across the sky. I turn around and check out the spectacular view behind me.

If you zoom in and look closely, you can see the red Mountain Gods Peru mess tent situated on the flat plateau ahead called Sisaypampa. After descending for a total of 2.5 hours, we follow the trail into Sisaypampa where the horses have already started grazing for their lunch. There is one other tent set up by another tour company. May I remind you that we were all together at Incachiriaska Pass just 2.5 hours ago. In that time, the Mountain Gods Peru crew has trekked down from the pass, set up the mess tent and toilet tent, set up our table and chairs, and are cooking lunch. I set my backpack out on the provided tarp and relax for a moment before being served with a pre-lunch beverage. A bowl of warm water also appears and I wash my hands and wipe them dry on a small towel.

After a bowl of warm soup, a massive spread of potatoes x2, beef, quinoa, carrots is put before us. There are bits of last night’s spaghetti in the quinoa and it looks like some of this morning’s left over scrambled eggs are mixed with the potatoes and carrots. Knowing that it’s all downhill the rest of the day, I heap a large second serving onto my plate. While we’re eating, the other group arrives and they look absolutely crushed. They sprawl out on the ground before dragging themselves into their mess tent. My lunch was a bit on the oily side and my stomach starts to rumble. Given the barren landscape with not much to hide behind, I’m quite grateful for the toilet tent. After our one hour lunch break, we hit the trail again at 1 pm.

Our lunch spot soon slips out of view as I find all sorts of new wonders before me. Colorful peat or sphagnum moss, Elaphoglossum mathewsii fern and some more Ephedra americana. The black spores of the Elaphoglossum fern are distinct and look like a serpent tongue.

We merge paths with the Pampacahuana creek before it cuts the canyon and descends below us.

Above: Looking back up Pampacahuana Valley.

Below: An animal pen built out of volcanic rocks.

The trail traces past erratics, an animal enclosure made out of rocks and a lovely outcrop of white Ageratina or Eupatorium?, Baccharis, peat moss, and Elaphoglossum ferns. We pass through a group of scattered cows who cautiously note our passage. A black and white calf almost seems like it wants to come over and say hi.

It’s about 2:30 pm when I look back up the canyon and the horses and crew are approaching us. So, they’ve cleaned up lunch and all the equipment required to cook, tents, table, chairs, loaded the horses and caught up with us in just an hour and a half. Best crew in the world!

It’s cool how the Jamesonia ferns look like little cobra snakes sticking up their erect heads. Andean blueberry Vaccinium floribundum or mortiño is highly reduced in size at this elevation. Ummm, sure hope that beautiful bull stays seated on the other side of the creek.

Suddenly, far in the distance there’s a black object in the sky. Here in Peru, it can only be one thing. The sacred Andean Condor is one of the largest flying birds in the world and central to Quechua and Inca culture. Their most important and sacred beings are the condor, puma and serpent. The condor or kuntur represents the celestial connection between the earthly world and the spiritual realm. It is believed that the kuntur carry messages to the gods and is the ruler of the sunny upper world. I point my camera at the condor’s little black dot in the sky and hope for the best. I watch it circle around for a few minutes before it disappears against the darkness of the mountainside.

Just about 3pm we round a bend in the canyon and a narrow line appears below us near a few small houses and farm plots. This treasure is an ancient Inca canal utilizing advanced engineering and water management skills. The canal, which is constructed from precisely cut and fitted stones, uses the gentle slope of the valley to easily move water down the canyon. The canal was an important part of the Inca’s extensive hydraulic network and is still used today by local farmers to irrigate crops. Pause and imagine for a moment about the construction involved to make this river stop meandering and to prevent erosion and landslides with effective drainage.

As we drop into the valley, we pass tall purple lupine and piles of potatoes. Elizabeth explains to me about how the potatoes are stored under the giant mounds of cut grass. She also explains how freeze dried potatoes or chuño are naturally made. One method involves placing the potatoes in water, then taking them out an drying them, then back in the water, dry again, back in the water, dry again until the full process is complete.

After we cross over the canal, we soon see a herd of sheep coming towards us. Behind them walks an elderly woman whose face is etched with wrinkles and Elizabeth speaks to her in Quechua. Elizabeth unloads some snacks and fruit into the woman’s skirt. I add a passion fruit as well. The woman smiles and seems very grateful. We part ways and the woman continues up the canyon with the sheep, presumably to the nearby houses.

We reach the end of the flat valley floor and then the trail starts to descend more steeply. We pass Telochistes flavicans or golden-hair lichen, Polystichum andinum, a type of shield fern and some more Ageratina. As we drop in elevation, flowering plants begin to flourish and line the trail. Salvia dombeyi or Giant Bolivian Sage looks just like the mole poblano salvia I have at home. But these are more like trees with large hanging flower masses. Brugmansia sanguinea, or red angel’s trumpet must tempt every good shaman.

What started high in the canyon as a creek, is now a full flowing river, which will continue its journey down to where it meets the Upper Urubamba or Vilcamayo River. The Urubamba, noteworthy for its proximity to Machupicchu and the train route from Ollantaytambo, is also one of the headwater rivers of the Amazon River. The Pampacahuana River rushes loudly to my left as the yellow Calceolaria slipper plant really burst with color along the trail edge.

Just after 4 pm we meet two cows coming our way up the narrow trail. We negotiate, and the bulls decide that we may safely pass without having to go for a swim in the Pampacahuan River. Negotiation includes some loud shouts and rocks.

5 pm clicks by and I do start to wonder how much farther. Purple ageratina and pink Barnadesia artfully distract me since I’m definitely starting to feel all the descent in my legs.

Just before 5:30 pm the terraces of the Paucarcancha Inca ruins fill the horizon. Oscar appears and we follow him downhill and cross country to our camp. Our home for the night is the yard of a local resident just below Paucarcancha. Look closely for the tiny orange dot which is my tent.

The yard is lovely and full of blooming begonias, fuchsias, roses, an almond tree, and a giant brugmansia. There is even a small bathroom with a shower. Certainly, the shower water must be cold water, so I opt for toweling off my body in my tent with the provided warm water. Our long descent has dropped us down to 10,270 and it feels quite warm out in comparison to last night and this morning. Elizabeth uses the cold shower to wash her hair. Then she also does some laundry which she hangs on a line that is strung across the yard. The horses are in a pasture on the other side of the fence from us.

We eat dinner inside a small utility room which is taking the place of our usual setup in the mess tent. A tarp is hung to separate the table from the area where the whole crew is cooking. I work on my journal and organize a few things in my tent before laying down for sleep about 9 pm.

3 thoughts on “Salkantay Day 2: Sunny Incachiriaska Pass And The Long Descent Of Pampacahuana Canyon”

Comments are closed.